by Samantha Pabich, MD

During the first months in my internal medicine residency continuity clinic, every patient problem—from a sore throat to a plantar wart—was a complex undertaking. As I watched and learned from my colleagues, many of these problems became easier to solve. One problem however, has not gotten simpler: weight management. In the past eighteen months I have had dozens of encounters focused on obesity, and yet I am not sure if these have translated to any significant successes. I am trying to say, “I’m in over my head.”

The burden of obesity is significant. More than 33% of the adult Americans are obese, 1 and the prevalence has increased over the past several decades.2 Obesity is associated with increased medical co-morbidity,3 increased pain,4 and lost productivity5. To a health system, obesity adds $1,429 annually per person to healthcare costs. 6

Given these enormous stakes, I’ve realized that the problem of obesity is too big for a patient and doctor to tackle alone: this is a problem that must be addressed by the health system and the community. To illustrate this point, I describe the case of “Linda Jones,” a character based loosely on patients that I have cared for in the past.

CLINICAL VIGNETTE

Despite having the best healthcare team available to her, Linda Jones died at the age of 51, from complications related to morbid obesity. In 1976, she had been a top athlete, having recently competed at the state high school swimming finals. In childhood, she had been “big-boned”, but in high school, she had transformed her five-foot ten inch body into a muscular frame weighing 77 kilograms (170 pounds). In nursing college, she lost her habit of regular exercise, and graduated at 79 kilograms (175 pounds), however was considerably less muscular. She got married when she was 22 years old and had a daughter two years later. Her doctor noted that if she breastfed, she would probably lose some of the 55 pounds gained during pregnancy; she opted to bottle-feed as she was working, and only lost 25 pounds. She and her husband separated in when their daughter was two years old, and during that year, she began overeating. In her early 30s, she weighed 117 kilograms (260 pounds), and remembers being seen by a doctor who recommended she lose weight; as a single working mother, she did not have much time to focus on exercise or healthy eating, and consistently put on 10-20 pounds per year. By her early 40s, she weighed 164 kilograms (362 pounds, Body Mass Index 51.9). She had seen her doctor regularly over the years with complaints of terrible chronic right knee pain, and had been advised to rest her knee, use ice, and take Acetaminophen. Her pain become so severe that she had a hard time walking; she was not eligible for a knee replacement given her weight. Her doctor filled out disability papers; she began using a wheel chair, and soon moved into a nursing facility. By her 50th birthday, her Body Mass Index had risen to 63, and it was difficult for her to get out of bed. When she was 51, she was admitted to the ICU in respiratory distress and died of pneumonia complicated by obesity hypoventilation syndrome.

I look back at cases like that of Linda Jones as a failure, not of any single person, but as a failure of the health system as a whole. The fault was not in the care that she received in the ICU, when Linda died, but rather in every year leading up to that, as her weight rose, and no intervention attempted to thwart it.

However, before placing blame on each of the doctors Linda saw over the years, we must also consider that Linda’s health system may not have supported her doctors in facilitating these discussions and interventions.

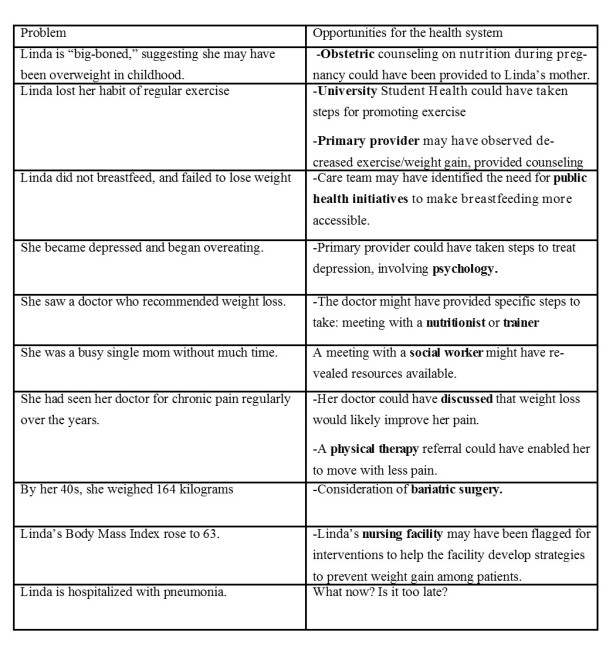

I created a problem list (inset) to identify failures that may have occurred in Linda’s life, and propose solutions to these. The left column dissects the story of Linda’s life, and where things went wrong. The right column discusses how being integrated into a health system, involving her primary care provider, along with other health care agencies and community organizations might have directed her life along a different path.

If Linda Jones were born today, it is difficult to say that her life would follow a significantly different trajectory than the one it took. However, it is within our power to create a health system and community partnership wherein she would not become obese as a young adult, disabled in her 40s, and deceased in her 50s. A public health approach is needed. All sectors of the community need to be involved, including community groups, private business, government individuals, and healthcare.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This commentary was developed while working with the Obesity Prevention Initiative team, that it funded by the Wisconsin Partnership Program, School of Medicine and Public Health, University of Wisconsin-Madison. Dr. Patrick Remington provided helpful comments.

REFERENCES:

- Ogden, C. L., Carroll, M. D., Kit, B. K., & Flegal, K. M. (2014). Prevalence of childhood and adult obesity in the United States, 2011-2012. Jama, 311(8), 806-814.

- Baskin, M. L., Ard, J., Franklin, F., & Allison, D. B. (2005). Prevalence of obesity in the United States. Obesity reviews, 6(1), 5-7.

- Burton BT, Foster WR, Hirsch J, VanItallie TB. Health implications of obesity: NIH consensus development conference. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord.1985;9:155-169.

- Hitt, H. C., McMillen, R. C., Thornton-Neaves, T., Koch, K., & Cosby, A. G. (2007). Comorbidity of obesity and pain in a general population: results from the Southern Pain Prevalence Study. The Journal of Pain, 8(5), 430-436.

- Colditz, G. A. (1999). Economic costs of obesity and inactivity. Medicine and science in sports and exercise, 31(11 Suppl), S663-7.

- Finkelstein, E. A., Trogdon, J. G., Cohen, J. W., & Dietz, W. (2009). Annual medical spending attributable to obesity: payer-and service-specific estimates. Health affairs, 28(5), w822-w831.

Samantha Pabich is a second year internal medicine resident at University of Wisconsin Hospitals and Clinics.